By Michelle Weyenberg and Jack Crittenden

[Editor’s Note: Read Part 1 of this story, How elitism is killing legal education, here. Read Part 2, Why do law firms focus on elite schools?, here. Read Part 3, Why do so many federal clerks come from the top schools?, here.]

Pepperdine Caruso School of Law is hopeful that Deanna Newton will be the next outlier when it comes to bucking elitism in hiring.

Newton, an African American woman, has many traits and skills that a law school would want in a new law professor: a minority member with smarts and practical law experience who will soon be a published author.

Whether she gets a good offer to become a law professor remains to be seen, because she is not a graduate of an elite law school.

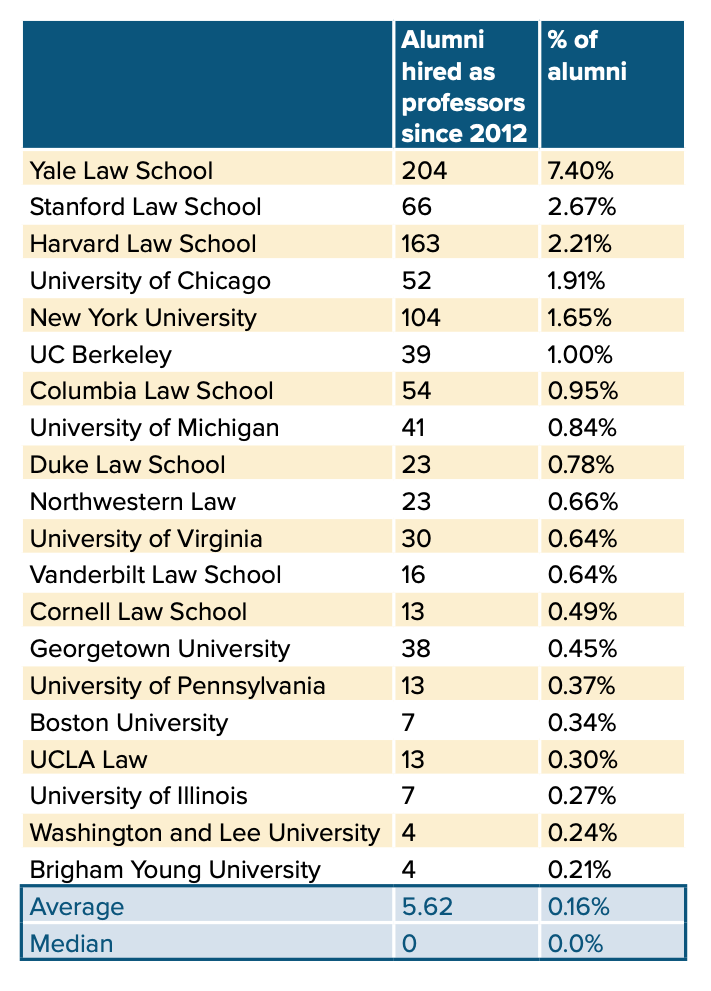

Based on data from the past 10 years, 72% of newly hired law professors came from the 15 most prestigious law schools. Thirty-four percent came from either Harvard Law or Yale Law.

The bias toward hiring grads from elite schools is worst at other prestigious schools. A 2019 article in the Journal of Legal Education reported that 95% of faculty members at the top 10 law schools went to a top-10 law school.

“Most prominent law schools publicly claim to strive for law faculty diversity,” the article says. “According to our examination of law school faculty, however, most schools are not meeting these goals.”

The article was written by Eric Segall, a professor at Georgia State University College of Law and a graduate of Vanderbilt Law School, and Adam Feldman, creator of the Empirical SCOTUS blog and a Berkeley Law graduate.

The bias in hiring can have major consequences for legal education. Segall and Feldman point out that how the top schools teach law has a huge impact.

“This inbreeding stunts creativity, experimentation and growth, and might even prioritize the theoretical over the practical to the detriment of the legal profession,” the article says.

Others argue that the bias is justified.

Stephen Presser, who graduated from Harvard Law and taught at Northwestern Law for 42 years before retiring in 2019, had a front row seat to the faculty hiring process.

“When hiring faculty, the objective indicator is who is going to write interesting articles and books about the law,” he said. “The key indicators were where you went to law school and where you clerked.”

Presser said law school, law review and class rank are pretty good indicators of who will be a successful professor.

But a study by Pepperdine Caruso Law dean Paul Caron and Rafael Gely, a professor at University of Missouri School of Law and a graduate of University of Illinois College of Law, found that law schools were under- and over-valuing certain attributes and thereby missing out on junior talent that goes on to produce highly cited scholarship.

The rank of the law school a person attended had no bearing on scholarly productivity, nor did membership on law review, a judicial clerkship, or a second advanced degree — basically every objective commonly used by hiring committees.

In 2014, Tracey George, then a law professor at Vanderbilt University and now the vice provost for faculty affairs, and Albert Yoon, a law professor at University of Toronto, authored a report based on data from a 2007-08 survey of law professor job candidates. They found that although law schools appeared to be open to candidates from non-elite schools in the early phases of the hiring process, few of them were hired.

“Institutional prestige is at best a proxy for quality,” their report said. “Nevertheless . . . the relative ranking of a candidate’s law school will be the single most important factor in predicting [academic] law job market success, beyond more direct measures of potential such as publications and teaching.”

The authors found that this insular approach to hiring could be problematic for the future of legal education.

“As law schools are called upon to reevaluate our goals and pedagogy, they rely on law professors who have a limited range of experiences,” the authors said. “Nearly all new hires in our study attended a small set of schools which are more likely to emphasize theory over practice.”

Hiring has changed since 2007-08, but not in the direction the authors would have preferred. There has been an increased desire to hire Ph.D.s with degrees from elite law schools and universities.

Caron said Pepperdine Caruso Law and other schools have created visiting assistant professor positions to help graduates buck that trend.

“The best predictor of a legal scholar is whether they have written before,” Caron said. “Folks who were productive scholars are more likely to succeed than those who went to Yale but did not publish.”

The idea of the visiting assistant professor program is to hire young practicing attorneys, such as Pepperdine’s Deanna Newton, who have done well but have not had the time or opportunity to do scholarship. The law school hires them for two to three years, they teach and faculty members mentor them on the legal scholarship game.

Newton, a tax lawyer, recently got her first scholarly tax article accepted for publication. The North Carolina Law Review will publish it.

“The hope is that when she enters the law professor hiring market, she gets a lot of offers,” Caron said. “This is one of the alternative paths that some schools are using to break the model.”

Breaking the model

Inbreeding, nepotism, elitism. Call it what you may. But breaking the model is hard.

“Talent management dynamics never gets the mindshare of law firm leaders,” said William Henderson, a professor at Indiana University Mauer School of Law – Bloomington. “The partners themselves have strong preferences to hire from elite schools.”

He said a hiring partner would need to educate his fellow partners about the importance of change, something few want to do.

“So everyone defaults to the elite heuristic,” Henderson said.

Alexander ”Sasha” Volokh, associate professor Emory University School of Law and author of The Volokh Conspiracy blog, who considers himself an economist, said hiring is difficult and time consuming; relying on one’s school is just easier.

“We have a lot of students that could compete well with students from Harvard and Yale,” Volokh said. “I understand why [those who do hiring] use this very crude and easy filter. In a sense, it’s terribly unfair. But it’s also very rational.”

Critics point out that, while hiring from elite schools may be easier, the importance of diversity and fairness dictate a different approach.

In their article, Segall and Feldman, lament what they call nepotism in legal hiring, labeling it as unfair.

“Are the faculty at the top-ranked schools willing to argue that only graduates of those schools are the most qualified to teach at those schools?” they ask. “There are hundreds if not thousands of graduates of excellent law schools outside the Top Ten who have had distinguished legal careers. Yet they have virtually no chance of obtaining a tenured position at a Top 10-ranked school.”

Henderson said change may come, but only when employers face economic pressures.

“Inertia is carrying this model forward,” he said. “It doesn’t make economic sense. But law school deans are not in position to the change the model.”

Henderson said, in the end, elitism in law graduate hiring is part of broader societal trends.

Sadly, those trends, one moving toward elitism and the another pushing for greater diversity, are on a collision course. Whether legal educators can rise to the occasion and enact change remains to be seen. Most are happy just the way things are.