When Ohio resident Erik Ehrenfeld started at Case Western Reserve University School of Law in the fall of 2024, the heated protests related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict had largely dissipated, but the topic was very much on the minds of students.

“There was and continues to be a lot of discourse regarding the current events in the Middle East, some of which was particularly intense, but civil,” said Ehrenfeld, now a rising 2L.

“I can remember that when I started here, I was very concerned as to whether the administration would allow students to speak their minds,” he said. “But to its credit, it has handled the situation pretty well.”

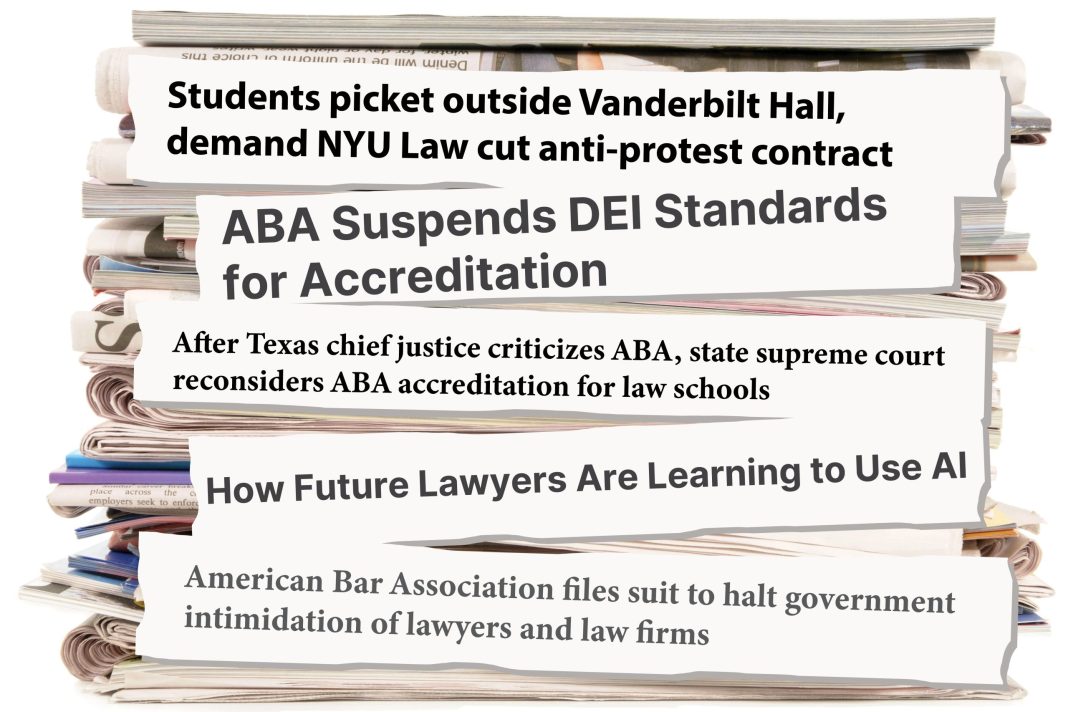

Freedom of speech is but one of many issues driving student passions, as diversity, equity and inclusion policies, the accreditation process and the job market itself continue to evolve, presenting students and administrators with a variety of new challenges.

The ability to express one’s views freely through protest and other means without the fear of punishment or retaliation is a value that many students continue to hold dear; the question is how do administrators ensure that the exercise of that right doesn’t lead to the destruction of property or make others feel unsafe?

Austen Parrish, dean of University of California, Irvine School of Law, and president of the Association of American Law Schools, said there are no easy answers.

“The country is facing difficult and polarizing issues right now,” Parrish said. “The communities in law schools are not uniform and are reflective of that reality.”

Free speech, safety and the law student dilemma

Over at University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, Dean Erwin Chemerinsky said there have been several incidents, particularly last year, which presented difficulties.

“Even though certain types of inflammatory speech may be protected, you can’t allow it to create a hostile environment,” Chemerinsky said. “It is the obligation of the school to maintain a safe campus while not punishing free speech.”

He said they have focused on a variety of methods including educational training and police protection where appropriate.

“While there’s a lot of anxiety over the Middle East, I think the Trump election has increased the tensions among students who are worried about deportations of foreign and undocumented students and the future of where the country is going,” Chemerinsky said.

At CWRU Law, Dean Paul Rose said administrators and faculty have worked with students to help them understand how to exercise their rights to free speech in productive ways.

“Students and faculty may have differing views on issues, but we do not prioritize one voice over another,” Rose said. “We encourage students to find ways to express their views authentically with mutual respect.”

CWRU Law rising 3L Melinda Week said the law school has served as the “Google” for the university in many instances, with students sometimes seeking advice on policies and answering legal questions.

“I appreciate that faculty members were willing to do this,” Week said. “It shows us that as lawyers it’s important to answer a client’s questions to the best of our ability.”

Boston University School of Law Clinical Professor Karen Pita Loor said the stakes have increased for student protesters, especially at law schools.

“Protesting has always carried the risk of arrest due to the expansive array of crimes at law enforcement’s disposal, which can be weaponized against protesters,” Loor said.

Now, she added, student activists’ fears have been compounded by some universities bringing disciplinary proceedings against their students and the House Education and Workforce Committee seeking information about such actions.

“As a result, what might have been a minor infraction can now lead to a full disciplinary investigation of a student that impacts the student’s career options and for noncitizen students, places them under the threat of deportation,” Loor said.

The possibility of arrest or disciplinary sanctions is of particular concern for law students, who must meet character and fitness requirements for admission to their chosen state bar, she added.

“Any arrest or disciplinary action must be disclosed to the bar regardless of the jurisdiction and will require an explanation by the student,” Loor said.

Loor said the potential of disciplinary actions presents a dilemma for students who may be planning to serve as advocates in the social justice or civil rights arena.

“Some students may have chosen to attend and been admitted to law school with the expressed goal of engaging in activism or pursuing careers as social justice advocates and yet the school counter-intuitively now takes punitive actions against them for activism,” Loor said. “Considering that schools admitted students with knowledge of their aspirations, it is inconsistent for universities to now penalize students for engaging in the very same acts that once made them attractive applicants.”

The erosion of DEI

With the 2023 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard striking down Harvard and the University of North Carolina’s race-based affirmative action programs in the admissions process together with the anti-DEI stance taken by President Trump’s administration, administrators and academic scholars alike are worried about what it will mean for legal education and the profession.

— Jonathan Feingold, associate professor, Boston University School of Law

BU Law Associate Professor Jonathan Feingold, whose expertise is in the fields of education law and anti-discrimination law, said the ongoing attacks on DEI make it more difficult for law schools to perform basic functions such as admitting a diverse student body.

“The Trump Administration has communicated that it is morally repugnant to have policies designed to produce racial equity,” Feingold said.

The efforts, he said, began in Florida ahead of the Trump Administration taking power with efforts to prevent educators, including law professors, from exposing students to the concept of structural racism.

“The Trump Administration has continued these attacks on law schools and the American Bar Association making it even harder for these institutions to incorporate core democratic values like racial inclusion and diversity,” Feingold said. “If future lawyers are not trained to understand why disparities arise in housing, education or the criminal legal system, they will not be well positioned to remedy it.”

Public law schools in California have not been impacted by legal changes related to the elimination of affirmative action since they have been prohibited from considering factors such as race, ethnicity or sex since Proposition 209 passed in 1996.

However, Chemerinsky said the cuts in federal grant money to the University of California system by the Trump Administration have been devastating due to grants of all sorts being cut, some of which simply because they are perceived as supporting DEI.

“Across the Berkeley campus we’ve had about $80 million of grants cut off from faculty and researchers,” Chemerinsky said. “Scientists have lost grants. In the law school, our Center for Law, Energy and the Environment and our Human Rights Center also have lost federal funds.”

There have been numerous lawsuits filed by universities fighting the loss of research funding.

Chemerinsky is co-counsel in one of these, a class action on behalf of University of California researchers who have had grants cut off. A federal judge in San Francisco ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and certified the suit as a class action.

“Although the Supreme Court prohibited schools from giving preference to candidates based on race, it did not prohibit schools from pursuing diversity as a goal,” Chemerinsky said. “The Trump Administration has vilified DEI, but we should want schools to pursue diversity, to treat people equitably and to be inclusive.”

Parrish said while the reductions in funding are primarily aimed at universities, they also impact their law schools.

“If research money is cut, law schools will almost certainly also see cuts,” Parrish said. “It usually trickles down.”

— Austen Parrish, dean, University of California, Irvine School of Law

In the wake of the Trump’s executive orders, Parrish said many schools are struggling with terminology related to DEI.

“I’m not aware of any school using racial criteria for admissions following the Supreme Court’s decision,” he said. “Schools strictly follow federal and state laws. Many admissions offices don’t even have access to demographic information, with that information hidden until after a class arrives on campus. Yet many schools have lawful programs, which are also now under attack, that seek to ensure that students from different backgrounds, including those from first-generation families and from families that are not wealthy have opportunities to access legal education and succeed.”

In addition to the uncertainty surrounding research funding, Parrish said legislation to cap and limit student loans may negatively impact lower-income and first-generation students.

“Federal actions making it more difficult for international students to study in the United States will harm not just universities but also local businesses that depend on and benefit from those students,” Parrish said.

States’ challenge to ABA oversight could upend law school standards

The American Bar Association Council of the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar currently accredits 197 law schools across the country.

This year, the supreme courts of Texas, Florida and Ohio announced that they are revisiting the requirement that students graduate from an ABA-accredited school to qualify for licensure.

Florida’s Supreme Court has appointed a workgroup to study the issue and “propose possible alternatives.” Texas has invited comments on whether to “reduce or end” reliance on council accreditation and Ohio has created a committee to study its nine schools.

There are 12 ABA-accredited schools with locations in Florida.

In the March 2025 announcement, the Florida Supreme Court said, “Reasonable questions have arisen about the ABA’s accreditation standards on racial and ethnic diversity in law schools and about the ABA’s active political engagement.”

The workgroup will submit its report to the court by Sept. 30, 2025.

In Texas, where there are 10 accredited law schools, the Supreme Court set a July deadline to receive comments from law school deans, the state board of law examiners, the bar and the public.

It is the council that is responsible for accreditation decisions, not the general ABA, said Jennifer Rosato Perea, managing director of the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar.

“The council is separate and independent from the general ABA,” Perea said. “Policies and statements of the general ABA are not representations of the council.”

The council has already suspended Standard 206, which requires law schools to demonstrate a commitment to diversity and inclusion, through Aug. 31, 2026.

“The council determined that as the higher education legal and regulatory landscape continues to change rapidly, this suspension would relieve law schools from the extreme hardship on them as they seek to comply with the law and accreditation standards,” Perea said.

In California there are a variety of options for students seeking licensure, including graduating from a council-accredited or state bar-registered fixed-facility law school as well as less traditional paths such as a registered unaccredited distance-learning or correspondence law school or studying under the supervision of a state judge or attorney.

Indiana and Connecticut also recognize online programs not accredited by the council.

While Texas and Florida would not be the first states to permit alternative pathways to licensure, Perea said the states could decide to make even broader changes.

For example, she said, they could determine that J.D. degrees from council-accredited law schools no longer satisfy a condition of licensure.

“The issue for students and graduates is that their degree may not be portable if they decide to practice outside of the state that issued their degree,” Perea said. “They may need to satisfy different educational requirements to practice in different states.”

Texas A&M University School of Law Dean Robert Ahdieh said even if changes were made to the accreditation process, they would not take effect immediately.

“There is no current alternative to the Council of the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar in Texas,” Ahdieh said. “Any change would simply allow for the ‘possibility’ of alternatives, and of resulting competition and potential improvement in the rules.”

He said part of the argument for change is the view that the council is over-regulating. Other critics are concerned that the council has prioritized diversity and inclusion initiatives they consider to be impermissible under current law, he added.

Ahdieh said there is one significant danger in shifting away from the council as the sole accreditor.

— Anthony Crowell , dean, New York Law School

“Today, a student from any accredited law school can sit for the bar and practice law anywhere in the country,” Ahdieh said. “If the accreditation framework should become fragmented, with law schools accredited by different institutions depending on location, we might lose that degree portability and the resulting national market for legal employment. Yet that is exactly what the legal profession has been pursuing in recent years, through the growing standardization of the bar exam across states.”

Anthony Crowell, dean of the independent institution New York Law School and a member of the executive committee of the AALS, said he believes having a national accrediting body for law schools is extremely important and should not be fragmented.

“I think having a patchwork of accreditors would be confusing and undermine rigorous and consistent programs of legal education,” Crowell said.

Chemerinsky said overall, the ABA has done accreditation well with its set of standards.

“Although I am often critical of how the ABA sets standards for law school accreditation, it is so important to have a national body without an ideological agenda doing this,” Chemerinsky said.

Geraldine Muir, associate dean for academic engagement at BU Law, said she’s not against taking a critical look at the accreditation process to see if changes could be made that would benefit students.

“Adding new viewpoints on the process could expand accessibility for more students,” Muir said. “Those who accredit schools should be as neutral as possible. Some states have added alternative paths to licensure, and I think it’s worth exploring different options.

Muir said even though she is open to questioning the process “that does not mean I do not support ABA accreditation as a standard.

“However, the world is changing, and we do need to adapt and change with it,” she added.

Political pressure puts law firm choices under fire

Since taking office President Trump and his administration have utilized a number of measures, including executive orders, which critics charge are designed to punish members of the legal profession and force law firms to change policies or cease representation of his political opponents, among other things.

While some major firms have challenged the orders or signaled support for lawsuits against the government, others have struck agreements with the administration.

On June 16, the American Bar Association filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in the District of Columbia against the government, more than two dozen federal departments and agencies and their heads.

In the press release, the ABA stated it’s asking the court “to declare unconstitutional the Trump administration’s ongoing unlawful policy of intimidation against lawyers and law firms and to enjoin the government from enforcing the policy.”

“It’s unclear what will happen with the ABA lawsuit,” Parrish said. “The attacks on judges and law firms, however, have been unprecedented because punishing law firms for the clients they represent is antithetical to the bedrock principles of our legal system.”

Parrish said lawyers must be able to take on unpopular cases and clients and should not have to worry about the government retaliating when they are simply doing their jobs.

“This is not a partisan idea, but a universal view held by lawyers across the political spectrum,” he said.

As the legal battle plays out, some students have said they won’t accept offers from firms that have not stood up to the administration and others are reportedly reconsidering those made by firms that have not taken actions.

“I think students are paying close attention to which firms fought back and signed amicus briefs,” Chemerinsky said. “I think this really matters to many people when they are selecting a place to work. If all firms fought back, they would have been able to succeed. By giving in, it only encouraged the administration to go after others.”

Crowell said he thinks law students are driven by values and institutional fit is important to them.

“I think it is important for law schools to help students find opportunities that work for them, and in my experience, students stay informed about what potential employers stand for,” he said.

CWRU Law students Ehrenfeld and Week said they are paying close attention to firms’ DEI policies.

“If DEI is a core value of a firm and they cave, it signals that they don’t stand up for what they believe in,” Week said. “If they don’t stand by their values, will they support me as an employee? I think a lot of my colleagues feel the same way.”

With many law firms saying they will continue to maintain their DEI policies, Ehrenfeld said, “We’ll see if they hold true to what they are saying.”

At the law school, Ehrenfeld said he’s hopeful administrators will continue to provide access to courses that explore the role of law in a multicultural society.

“All schools are subject to changing postures on DEI,” Ehrenfeld said. “For example, I took a Race, Law & Society course and there’s some concern over whether that class will continue to be available. So far, I think it’s still listed.”