By Michelle Weyenberg and Jack Crittenden

[Editor’s Note: Read Part 1 of this story, How elitism is killing legal education, here. Read Part 2, Why do law firms focus on elite schools?, here.]

Brittany Kubisch was one of those lucky few.

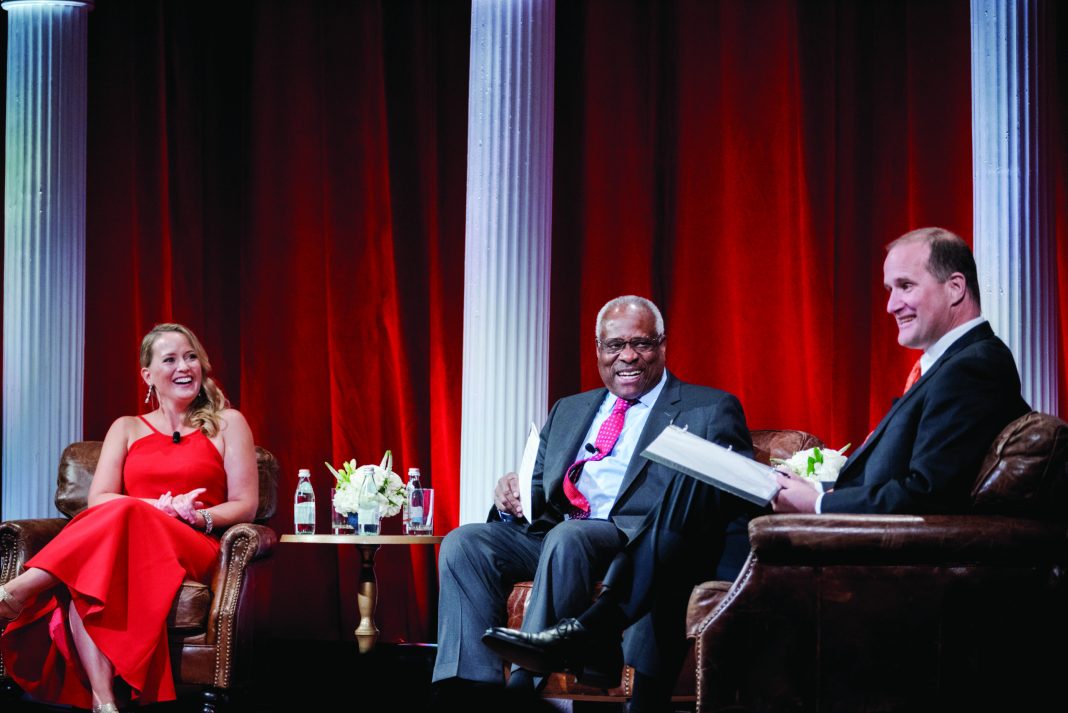

A 2012 graduate of Pepperdine Caruso School of Law, she landed a coveted federal clerkship with the Ninth Circuit, followed by one with the Sixth Circuit. That led to a clerkship with Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas during the 2017 term.

Only 6% of Pepperdine Caruso Law graduates land federal clerkships, and even fewer move on to the Supreme Court. Kubisch was the first Pepperdine graduate in nine years to do so.

It’s difficult for any graduate to secure a prestigious federal clerkship. It’s even more challenging when you don’t graduate from one of the most prestigious law schools.

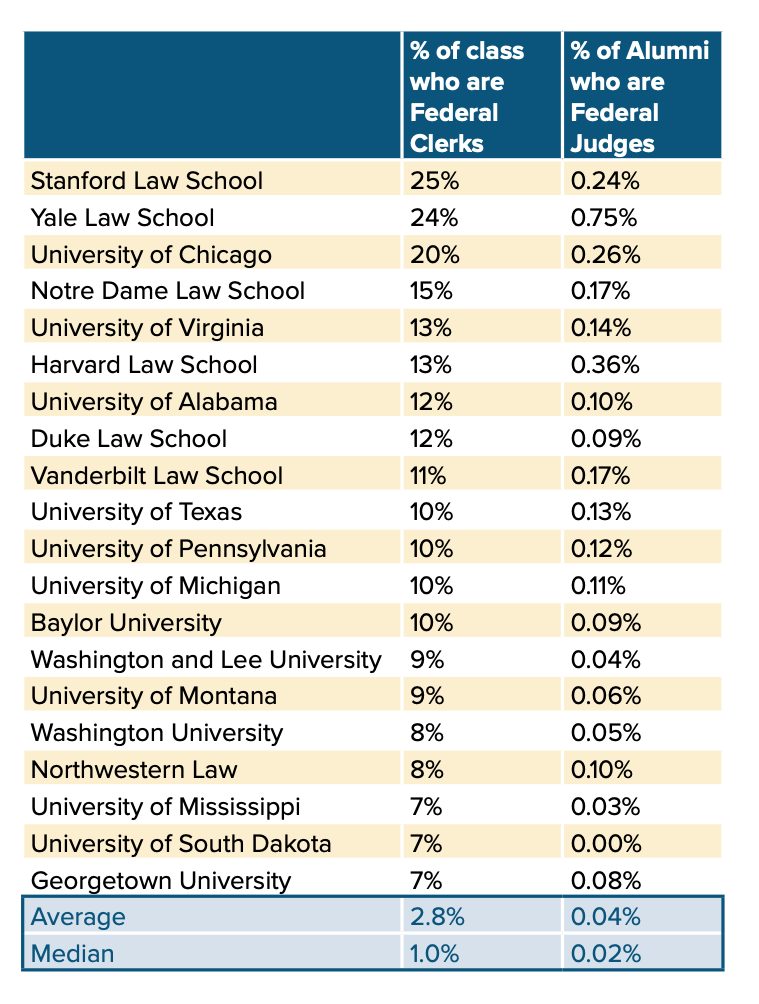

The most recent American Bar Association data shows that 46% of all federal clerks are graduates of one of 15 elite law schools. Meanwhile, 44 law schools saw no 2022 graduates land federal clerkships, and 65 schools had only one or two. Pepperdine Caruso Law, at 6%, ranks 22nd in the nation for federal clerk placement.

The focus on elite schools carries over to federal judges as well: 44% are graduates of the 15 most prestigious law schools.

Commentators have long noted that the demographics of law clerks does not align with the general law student population when it comes to socioeconomic background, gender, race or ethnicity.

Jeremy Fogel, executive director of the Berkeley Judicial Institute and a Harvard Law graduate, wanted to know why. So he and two co-authors, asked 50 federal judges how they hire clerks.

The study, titled “Law Clerk Selection and Diversity,” identified eight key findings, including that judges from the top 20 schools are significantly more likely to hire clerks from the top 20 schools.

“I understand the [students’] experience [at] the top schools better,” said one anonymous judge who was quoted in the study. “I have lack of familiarity with non-top schools; I wouldn’t know how to evaluate candidates from those schools.”

Another anonymous judge, who has hired clerks from schools outside the elite, said it’s easier to use top schools as a measurement to fall back on.

“A big part of our finding was that judges who had very diverse clerks were willing to depart from the conventional criteria of top law schools,” said Mary Hoopes, a law professor at Pepperdine University who co-authored the study. “They would say things like, ‘I just am not confident that every clerk who’s capable of doing good quality work just happened to go to one of four or five law schools.’ And instead, they had a lot more confidence in this idea that it wasn’t taking a risk to hire someone outside of an elite law school.”

The study found that the judges most willing to hire from non-elite schools were Republican-appointed judges, women, minorities and judges who graduated from non-elite law schools themselves.

Justice Thomas, who hired Kubisch, fits two of those four criteria: Republican-appointed and a minority.

“We talk about being fair and choosing people on merit,” Thomas said at a Pepperdine event in 2019. “The court is all Ivy League, and the law clerks tend to reflect that. That is fine, but there are smart kids in other places. I like kids who are hungry . . . who don’t feel like they are the noblesse oblige.”

The study showed that 76% of judges who did not attend a top 20 school hired at least one-quarter of their clerks from schools outside the top 20, whereas only 34% of judges who attended a top-20 school did so.

“I start from the premise that I didn’t graduate from Harvard, Yale or Columbia,” one judge said. “I want to be a living witness to the fact that you can find excellence in a lot of places.”

Many judges give preference to candidates from nearby schools, regardless of ranking.

“Local schools get a leg up,” one judge said.

The data shows that locality is a major influence, benefiting regional schools such The University of Alabama School of Law, Baylor University School of Law and Alexander Blewett III School of Law at University of Montana.

According to the study, University of Alabama placed 12% of its graduates in federal clerkships, putting it at 7th in the nation for clerkships as a percentage of graduates.

William Brewbaker, law dean at University of Alabama, said placements from his school are especially strong in Dallas and Houston. But there are also placements in Washington, D.C., New York City and Chicago.

Baylor Law placed 13th for federal clerkships, and University of Montana placed 15th.

The study found that judges with trusted relationships with a school’s faculty were more likely to hire from that school.

Paul Caron, dean of Pepperdine Caruso School of Law and a graduate of Cornell Law School, said Pepperdine Caruso Law makes a point of engaging with judges. The school invites judges to participate in its moot court competitions, symposiums and other events. It often has students pick up visiting judges at the airport, giving the students one-on-one time with the judges — something the school hopes will lead to more clerkships.

Most judges who hire outside the elite don’t regret it.

The Berkeley study said judges had nothing negative to say about the job performance of clerks who had attended non-elite schools.

One judge said the work product of his clerks from less elite schools was “just as good as anything I’ve received from a clerk [from] Yale or Harvard.”

Still, most judges, especially those who want to be feeders — those who help promote clerks to the Supreme Court —tend to favor grads from elite schools.

One judge said it is unfortunate but a reality that being a feeder means hiring “at the top of the class” from Harvard, Yale, Stanford or University of Chicago, and not from state schools.

Another said he considers applicants from “maybe 10 schools” and relies heavily on “a small number of professors at a narrow range of schools.”