In January, I wrote about why U.S. law schools enjoyed a position of strength as a destination for global LL.M. aspirants. But I also provided caution that other factors could negatively impact those decisions.

I wrote:

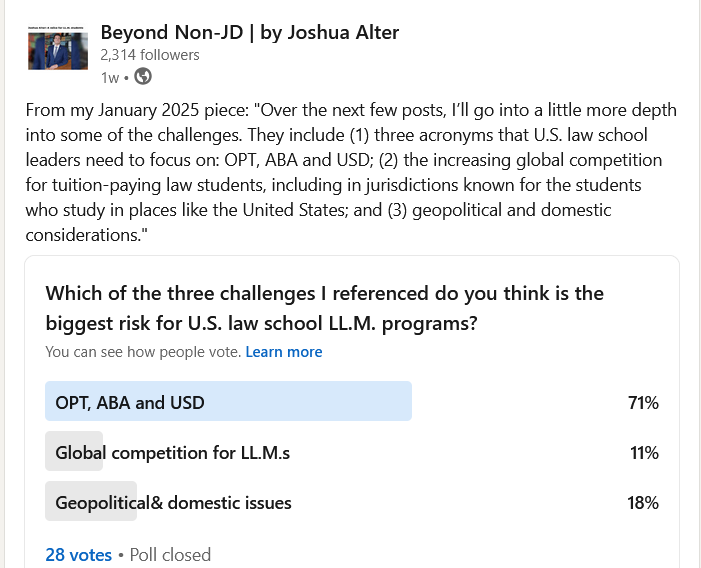

Over the next few posts, I’ll go into a little more depth into some of the challenges. They include (1) three acronyms that U.S. law school leaders need to focus on: OPT, ABA and USD; (2) the increasing global competition for tuition-paying law students, including in jurisdictions known for the students who study in places like the United States; and (3) geopolitical and domestic considerations.

I asked Beyond Non-JD readers to share their thoughts on which they believed posed the biggest challenge. Only 28 readers responded, but they overwhelmingly focused on the three acronyms I listed first. This month, I’ll discuss how issues surrounding them can chip away at the U.S.’s leading position for LL.M. students.

First, a caveat

LL.M. students are not monoliths. And that applies to residential, foreign-educated LL.M. students. LL.M. programs are composed of very different students with very different situations and very different goals.

U.S. citizens and green card holders with foreign first law degrees join LL.M. programs designed for foreign-educated lawyers. Add to that others who do not need or will not need work authorization and those not necessarily looking to work in the United States upon graduation.

Not everyone needs to navigate Optional Practical Training (OPT). Not everyone is looking at the LL.M. experience through the J.D. lens and expectations. And not everyone is paying for their LL.M. program through a foreign currency.

In this article, I focus on those abroad who will study in the U.S. on a student visa, typically an F-1 visa. And within that group, those who want, or at least are open, to working in the U.S. upon graduation.

So, what may make them reconsider their global options?

Optional practical training and working in the U.S.

Concerns around the future of OPT are in the news. Questions surround finding a balance between the revenue international student tuition brings (directly and indirectly) and the desires international students often have to work in the U.S. upon graduation.

Law schools are by no means an outlier within higher education. Speak with international LL.M. students as often as I do, and you’ll hear them talk about their interest in good jobs in the U.S. upon graduation. Part of that is because they often plan to become licensed attorneys in jurisdictions such as New York, California and Texas; part of that is because they want to earn U.S. salaries to justify the costs associated with an LL.M., at least in the short and medium terms; and part of that is because they often choose the U.S. because of OPT as an attractive selling point.

The U.S. may have an access to justice gap, but it does not have a law school graduate shortage. Every year, there are J.D. students who cannot secure jobs as lawyers, especially for the types of salaries that justify the costs involved. So it’s not a surprise that some LL.M. students, especially straight from LL.B. programs and those without strong pre-LL.M. credentials, struggle to secure decent-paying post-LL.M. jobs — if they can secure any paid job at all.

But at least now there is a path to employment for F-1 graduates.

Is OPT going away? I can’t say. And I don’t think it will as of February 13, 2025.

But what if the program is revised? Especially in majors that are not thought of as “critical” to fill shortages in?

Even with more restrictive OPT requirements (e.g., minimum salary), schools would have a harder time with one of their stronger selling points in the global race for LL.M. students.

American Bar Association and where LL.M.s fit in U.S. law schools

My career and platform exist, in large part, because of the ABA’s distinction between J.D. and Non-J.D. programs and students. This is not a secret and I encourage all prospective LL.M. students to read how these programs are described on the ABA’s website. Non-J.D. programs are primarily designed as revenue generators, lack the same consumer protection disclosures as J.D. programs, and are generally seen as designed for different purposes than J.D. programs.

So much of the tension I see and hear in the LL.M. world is from students who didn’t know or didn’t truly understand the differences when they applied and started their programs. I notice a gap in experiences and outcomes for LL.M. students, and I think those who are informed, do a lot of research and find really great programs for their personal goals and financial situations tend to better than those who do not.

Each time LL.M. students feel like secondary students at their law schools, it hurts the ability of schools to recruit. And more LL.M. students are speaking openly about the challenges of their experiences, especially on LinkedIn. In positive ways, I’ve noticed that this pressure has helped shift more resources to LL.M. students. Information is power. Advocacy is power.

As long as U.S. law schools think J.D. first, Beyond Non-JD serves a purpose to help share information with LL.M. students. Ultimately, schools have to decide where LL.M. programs and LL.M. students fit into their revenue-generating Non-J.D. operations. And LL.M. prospects can decide if the LL.M. is “worth it” given their goals, financial situations and risk tolerances.

Negative publicity may lead more LL.M. prospects to consider U.S. J.D. degrees or choose LL.M. programs in other jurisdictions as they decide where to make their educational investments from abroad. Though to be fair, F-1 employment can also be challenging for J.D. students. The U.S. continues to enjoy other great advantages while many other jurisdictions face similar issues around employment for international students.

United States dollar and currency concerns for those abroad

And speaking of costs, U.S. law school sticker tuition has risen considerably over the last 10 to 15 years.

And while discount rates have also increased, the stories I see are often focused on J.D. discount rates, including through ABA 509 data sharing the percentage of J.D. students who receive specific ranges of scholarships.

While I have noticed LL.M. discount rates appear to move up (and people speak more openly about LL.M. scholarships), LL.M. and other Non-J.D. students are still expected to generate revenue. Sometimes to subsidize those increasing J.D. scholarships.

And while sticker tuition rises, many foreign students also face a second reality check when it comes to currency conversions. A stronger U.S. dollar may be great for us. I certainly enjoy it here in Bali ($1 USD was about 16,300 IDR at the time I wrote this). But it’s not great when schools share tuition prices online or at the end of PowerPoint presentations.

This is where LL.M. students abroad face a different challenge than U.S. citizens and green card holders already in the United States who take out student loans or pay through U.S. savings. To secure the F-1 visa, a student needs to show the funds for Form I-20.

With currency fluctuations on top of exchange rates and expensive tuition by global standards, at a certain point U.S. law schools may price out even more of the most promising foreign lawyers than they already do for LL.M. programs.

U.S. education already prices out so many people around the world. But if LL.M. degrees are not priced to reflect foreign currency realities, even more students from abroad will need to choose other options.

Conclusion: Not all doom and gloom

U.S. law schools continue to enjoy strengths due to its legal system, legal market and the strong reputation of its schools. State bar exams are becoming more welcoming overall to LL.M. students. LL.M. graduates move into J.D. programs, settle down through family-based immigration, and secure employment-based visas with strong LL.M. credentials and great networking skills.

Online LL.M. programs and hybrid LL.M. programs take away some of the cost-of-living pressures. And more U.S. law schools are focused on domestic Non-J.D. students, especially through degree programs for “non-lawyers.”

There is more talk about the relative ease of securing LL.M. scholarships to help more people consider LL.M. programs, and some schools, especially state schools, are priced to be competitive globally.

International students and graduates I speak with are still interested in U.S. LL.M. programs. But there is a need to make sure law schools are focused on the things that will help welcome foreign students. Some issues may be easier for U.S. law schools to control or at least steer, while some are unrealistic or even impossible, but it’s important to understand and think through the challenges.