Legal education is more diverse than ever, but that could all change in the blink of an eye. And law schools are preparing for that.

Legal education stands at a crossroads. For years, law schools have sought to match enrollment with the real world’s makeup of race, gender and other underrepresented groups.

Yes, the American Bar Association requires law schools to demonstrate a commitment to diversity in both students and faculty. But many schools have gone above and beyond that accreditation requirement.

In 2018, law schools hit a zenith for diversity. With minority enrollment numbers higher than ever, an unprecedented 80 law schools out of 204 made our honor roll for diversity. Inclusion on the honor roll was based on how well enrollment matched national averages for various races.

But a different ABA requirement began chipping away at diversity. The ABA passed a new rule stating that law schools must attain a bar passage rate of 75% within two years of graduation.

Several law schools found themselves with bar passage rates either below that mark or dangerously close to it.

The new standard contributed to the closing of three law schools that received honors for diversity in 2019. Two other law schools dropped ABA accreditation to avoid a similar fate.

The loss of those schools meant a hit to diversity. At the same time, racial protests in 2020 brought diversity to the fore, with law schools doubling down on their commitment to enroll a diverse student body. Law schools across the nation raised money for scholarships and created endowments to support diversity.

The conflicting trends have brought legal education to the aforementioned crossroads. Law schools desperately want to improve diversity but are finding it increasingly difficult and complicated. And pending Supreme Court decisions could make it even more challenging.

The Supreme Court is expected to rule in June on two affirmative-action-related cases. Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina accuse the schools of discriminating against Asian-American applicants.

The plaintiff is urging the court to overturn a 2003 case, Grutter v. Bollinger, which allowed race to be used as a factor in college admissions to help achieve student body diversity.

With the current conservative court, most expect the plaintiff to prevail.

“If affirmative action falls, we can expect to see a lot of educational institutions drop objective standards from their admissions practices,” John Sailer, a fellow at the National Association of Scholars, told the Daily Caller News Foundation. “This allows them to continue race-conscious admissions by other means. Already, we see schools embracing this workaround.”

He said law schools are preparing for the U.S. Supreme Court to strike down — or seriously weaken — the ability of schools to use affirmative action practices in their admission decisions. If that happens, schools will not need to be as dependent on such concrete metrics as the LSAT.

The good news is that legal education is more diverse than it has ever been. Despite the fact that fewer schools made our honor roll this time around, overall diversity numbers in legal education are up. ABA data shows that 36.6% of incoming students identify as people of color, up from 34.1% in 2020 and 33.3% in 2018. The data shows that 57.7% of first-year students are white, 9.4% are Hispanic or Latino, 8.9% are Asian, and 7.8% are Black.

Still, legal educators feel pressure to improve upon those numbers.

“Regrettably, the law remains the whitest and most male-dominated of the professions, even though society is increasingly more diverse,” said Colin Crawford, dean of Golden Gate University School of Law in San Francisco. “Legal education needs to focus on turning out more diverse lawyers who are well-equipped to effectively represent and serve diverse clients.”

Golden Gate is facing its own issues. The private law school has been ranked high on our list of most diverse schools for several years, coming in at No. 5 this year. But the school has struggled with bar passage.

Golden Gate’s Class of 2018 had a bar passage rate of 57.5%. In 2019, the number improved to 67% but still fell below the required 75% mark.

Facing the risk of losing accreditation, the school drastically reduced the size of its entering class — from an average of 220 students in prior years to 45 this year.

“It is our belief that with deliberate effort, one can both achieve strong bar pass results and also produce a diverse class,” Crawford said.

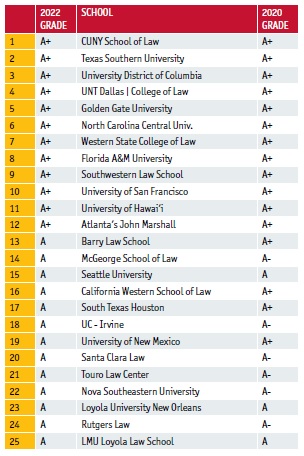

He said he is hopeful that this dramatic approach will allow the school to continue to fulfill its mission of helping to diversify the legal profession. Golden Gate moved up on our list of most diverse schools from No. 8 in the last ranking two years ago to No. 5 this year. The 12 law schools that received an A+ in 2021 were able to maintain that grade this time around. But that number is down from 20 schools in 2019.

City University of New York School of Law is ranked No. 1 this year, up from No. 3 last time.

Texas Southern University – Thurgood Marshall School of Law in Houston remains at No. 2. The Historically Black College also has a strong Hispanic population in addition to Black students.

University of the District of Columbia David A. Clarke School of Law is No. 3 in this year’s ranking, up from No. 7 last time.

University of North Texas at Dallas College of Law, which was No. 1 last time around, came in at No. 4 this year.

The ranking compares each school’s percentage of minority faculty and its percentage of students in five racial groups to national averages. Those five groups are Asian (which includes Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders), Black, Hispanic, Caucasian and Native American.

The study rewards schools for providing a mix of races. That is why Howard University, with a student body that is 94.2% Black, for example, does not make the list. Schools are given credit for exceeding the national average for any one race by up to 30%.

Now, the bad news: The legal profession continues to lag when it comes to diversity.

Out of 2,396 elected prosecutors in the United States, only eight identified as Asian American in a study by the American Bar Foundation and the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association.

And new employment numbers from the National Association for Law Placement show that while 81% of white law school graduates were employed in bar-passage-required jobs, only 65.9% of Black graduates were so employed, followed by Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander graduates at 58.5%.

“We continue to see that race, gender and the level of parental education have profound effects on employment and salary outcomes after law school graduation, and we do not see those gaps closing over time,” said James Leipold, NALP’s former executive director. “I continue to believe that the entire profession, including law schools and legal employers, has a shared responsibility to work deliberately to close these gaps.”

Many believe changing law school admission policies is an important step toward creating a more diverse legal profession.

“People are so much more than scores,” said Degna Levister, associate dean and director of Pipeline to Justice at CUNY Law. “Our application review process is holistic and whole-person focused.”

Levister said students’ personal experiences with injustice and how they have overcome obstacles often determine their ability to succeed in law school and on the bar exam.

Nicole Smith Futrell, director of the Center for Diversity of the Legal Profession at CUNY School of Law, stresses the importance of making law school available to individuals from all backgrounds.

“Legal education is the central access point to a profession that is responsible for promoting justice and equal rights,” she said. “Those from underrepresented groups, such as Black, Latinx, Indigenous, LGBTQIA and disabled people, have personal and social histories that reveal where equal justice repeatedly falls short in our country.

“Underrepresented students should be encouraged to obtain legal education in a diverse and inclusive environment that both values their experiences and supports their individual professional potential and needs.”

Golden Gate University’s Crawford said meeting people from a variety of backgrounds and experiences enriches all of us. A diverse class brings a wider variety of perspectives and often leads to greater understanding and insight.

As a result, he said, students are likely to become better lawyers and more empathetic citizens.

“Historically, people from minoritized backgrounds have not been allowed prop er, equitable access to legal education,” Crawford said.

“[Clients] are likely to feel more comfortable working with those who understand their circumstances and experience. If lawyers have similar cultural, social and economic backgrounds and experience, they can better connect with and represent their clients’ interests.”

Many law schools, law firms and organizations are jumping on board in an effort to create more diversity in the profession.

Vela Wood, a law firm in Texas, has partnered with Kaplan, a global educational services company, to offer free LSAT prep courses to Black students.

AccessLex Institute gave a $40,000 grant to NALP to enable law schools with significant numbers of students from groups underrepresented in the legal profession to participate in the annual Law School Alumni Employment & Satisfaction Study. The data from these schools’ alumni will enhance the study’s inclusivity.

But perhaps the best initiatives are the ones that recognize and embrace the value of diversity.

“Admissions goals may boost diversity numbers, but it doesn’t automatically create an inclusive culture,” said Danielle Boardley, assistant dean for diversity, inclusion and student life at Drexel University Thomas R. Kline School of Law

“Increased diversity within community, coupled with inclusive efforts, helps to establish a sense of belonging for everyone. Research shows that having a connection to an organization or group of people that makes you feel you can be yourself not only results in greater engagement, it’s also a psychological need.”

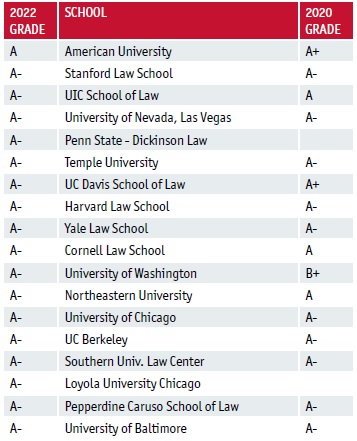

Most Diverse Law Schools Methodology

Our grades are based on how well each school matches with the U.S. average for each minority population. For students, we look at Asian (which includes native Hawaiian), Black, Hispanic, Caucasian and American Indian populations. For faculty, we compare overall U.S. minority percentages with the percentage of minority faculty. A school receives full credit when it matches the national average and can receive up to 40% added value when its percentage is higher than the national average for each population. Faculty accounts for 25% of the final grade, with each student population accounting for 16.67%, except for American Indian, which accounts for 8.32%. We’ve used this methodology since 2013. All data is from the American Bar Association.