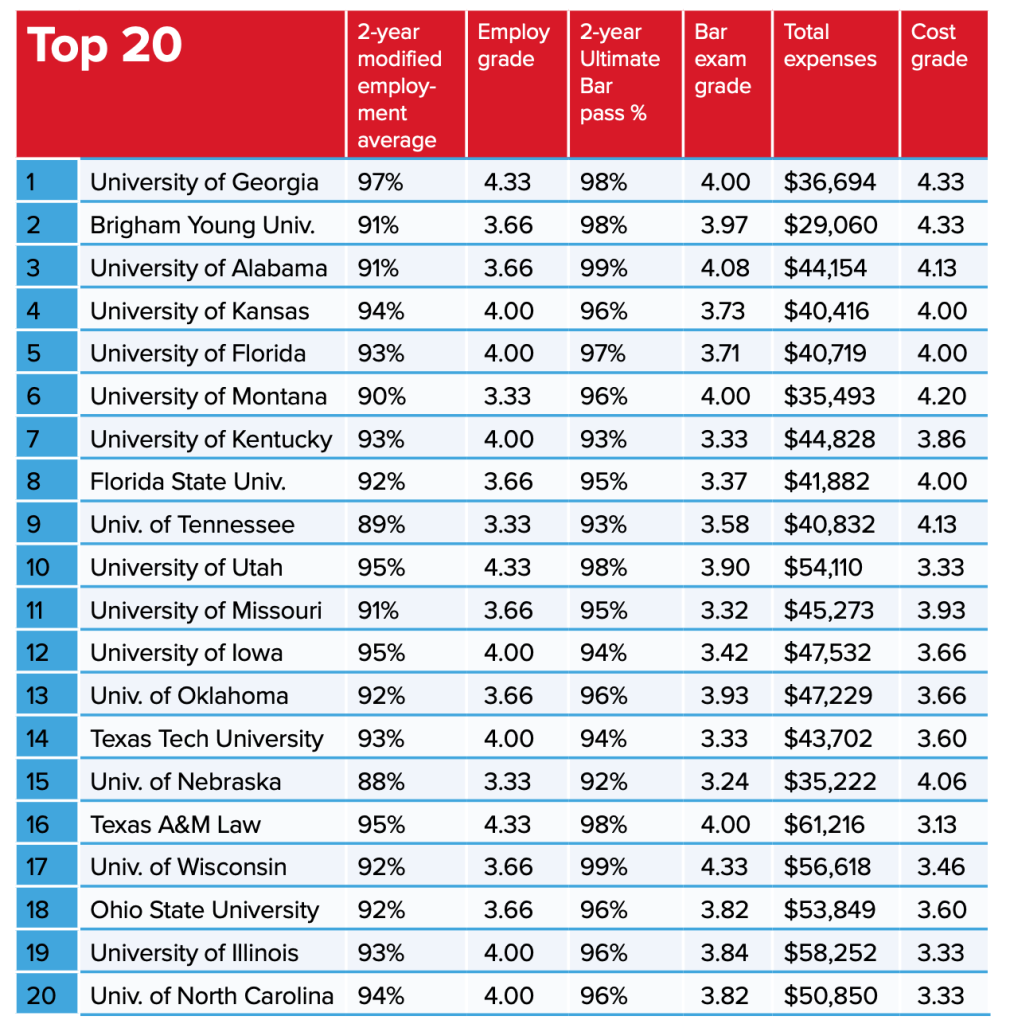

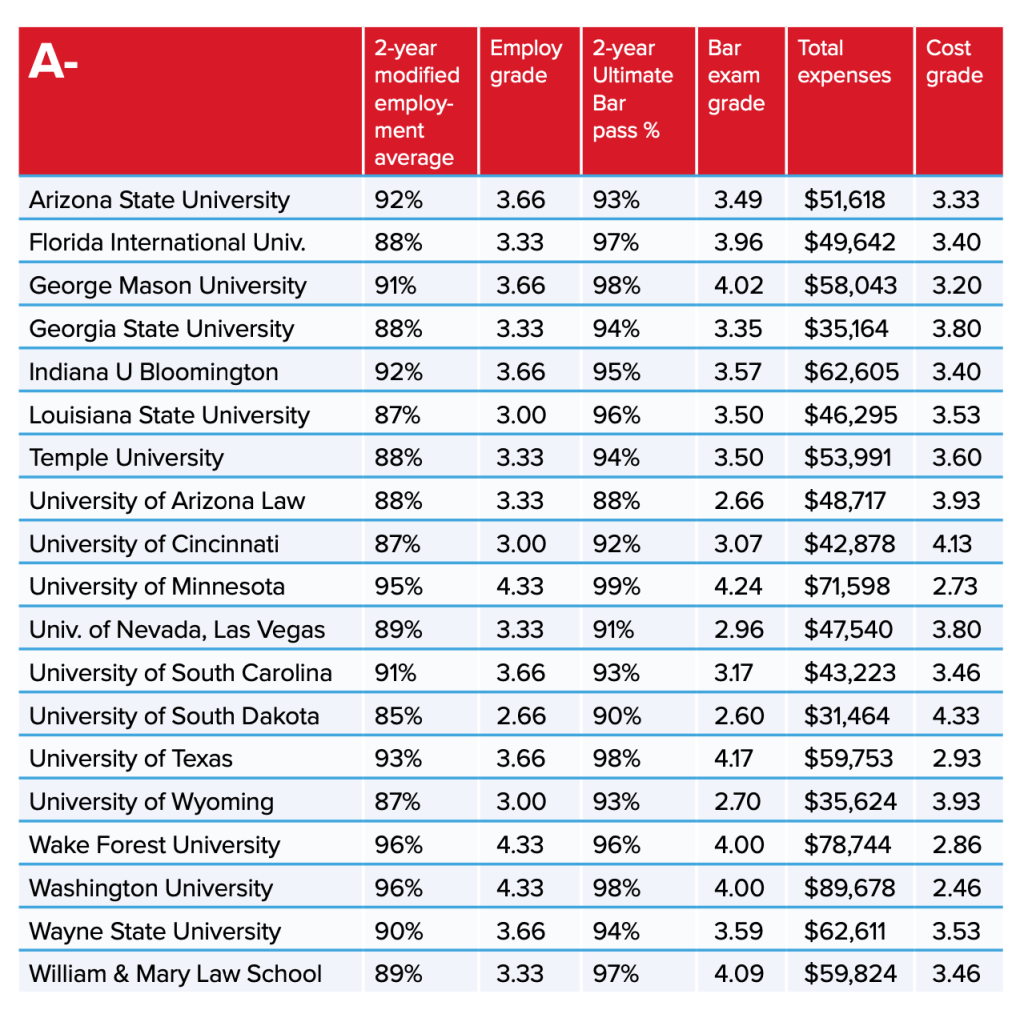

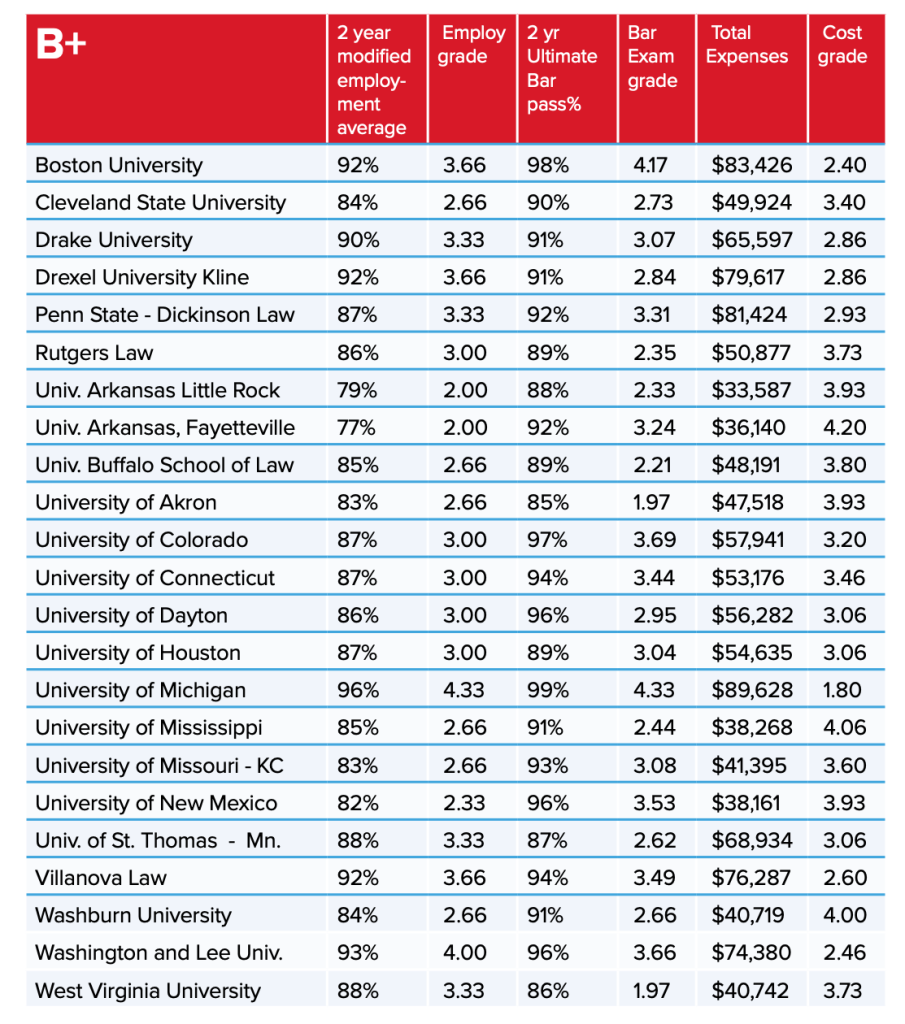

University of Georgia and BYU dominate our annual ranking based on cost, bar exam performance and graduate employment.

When Carolina Mares decided to apply to law school, she knew two things.

First, the Atlanta middle school teacher wanted to pursue a career in public interest. Second, she didn’t want to graduate with an overwhelming amount of debt.

“I focused on schools that were offering a substantial amount of scholarship support or did not have exorbitant tuition rates,” said Mares, who taught French and Spanish for 10 years.

Fortunately, she found multiple options that met her financial criteria, so she turned her focus to other key factors such as bar passage rates, graduate employment outcomes and federal clerkships.

In the end, she opted for University of Georgia School of Law in Athens, and it provided her with a generous scholarship package.

“For me, UGA was the obvious choice,” said Mares, now a second-year law student. “While the financial aspect was important, UGA offers exceptional outcomes as well as accessible programs and externships that allow students to explore a number of career options.”

During the summer of 2023, she participated in a two-week study-abroad program in Belgium and the Netherlands, which focused on economic and human rights. She also had an externship at a law firm in Tunisia, which allowed her to delve into and develop a passion for international arbitration.

“I would not have been able to take advantage of either opportunity had I been saddled with burdensome loans,” Mares said. “Since my interests have broadened, I find myself less certain about my post-graduation plans and appreciate having the freedom to explore a variety of practice areas.”

University of Georgia is No. 1 on preLaw Magazine’s Best Value Law School list this year. Selections are based on a school’s graduate employment rate, bar passage rate and overall cost, including tuition, fees and living expenses.

These are all factors that UGA Law Dean Peter “Bo” Rutledge said the school uses to gauge its own performance in the legal education market.

“Our mission is to be the nation’s best return on (students’) investment,” Rutledge said. “We define the value we provide both quantitatively and qualitatively.”

University of Georgia leads a list of 52 public universities and 10 private law schools that earned cumulative grades of B+ or higher for value. To determine our ranking, we assigned grades to each school for cost, employment and bar passage. The final GPA was then calculated with cost accounting for 55% of the final GPA, employment 30% and bar passage 15%.

This was the first year that preLaw assigned grades for each category and then determined an overall GPA. In the past, we simply assigned each school an overall score.

Despite the change in methodology, there were few changes in the ranking. In fact, it has been fairly constant over time, with 18 of the top 20 schools being ranked high for the last nine years.

While UGA moved up from No. 2 to No. 1 this year, it was No. 1 from 2018 to 2020. Brigham Young University – J. Reuben Clark Law School dropped from No. 1 in 2021 and 2022 to No. 2 this year.

Only six law schools failed to repeat from last year, and nine newcomers joined the list — each with a B+.

Newcomers are: University of Akron School of Law; University at Buffalo School of Law, The State University of New York; Boston University School of Law; University of St. Thomas School of Law-Minneapolis; The University of Michigan Law School; Drake University Law School; Cleveland State University, Cleveland-Marshall College of Law; University of Dayton School of Law; and University of Arkansas at Little Rock, William H. Bowen School of Law.

Despite the consistency in the ranking, legal education has seen a lot of change in the past 10 years. Overall employment outcomes and bar passage rates have improved, and costs have dropped.

In other words, legal education is a far better value than it was 10 years ago.

More affordable

Ten years ago, legal education was in crisis.

Starting in 2008, thousands of students scurried to law school to wait out the Great Recession. But the recession hit the legal industry hard. Prior to the recession, the largest law firms hired more than 5,000 new graduates annually. In 2011, that number dropped to 2,900.

The New York Times, The Atlantic and online blogs criticized law schools for producing too many graduates with high debt and not enough job opportunities.

That led to an unprecedented decline in applicants. While 91,000 applied in 2010, the number fell to 57,000 in 2015. Faced with such a drop, law schools began to innovate their curricula, shrink their class sizes and offer more scholarships.

The increase in scholarships effectively lowered the total cost of attendance, which led to a gradual decline in law student debt. For example, in 2012 the average debt for law students who borrowed money was $100,000, which is equal to $130,000 today when adjusted for inflation. This year, the average debt was $111,400.

That equates to an average of $80,769 for all students (whether they borrowed or not), down from $81,040 in the prior year. Average debt is only $56,900 for our 62 Best Value honorees.

University of Georgia has been at the forefront of this change. Rutledge said the school is using a four-pronged strategy to ensure accessibility and affordability for students.

Resident tuition for the 2023-24 school year is $18,994, including fees.

“The cost of attending our institution has actually gone down from what it was in 2015,” Rutledge said.

That year, resident tuition and fees totaled $19,476.

This year’s nonresident tuition and fees are $37,752, up only slightly from the 2015-16 school year when the cost was $37,524.

These numbers are even more significant when inflation is factored in.

This year, average law school tuition and living expenses grew by 3.5%, which was far below the 8.2% rate of inflation.

Meanwhile, salaries are rising at a fast rate. The mean starting salary for law graduates in 2015 was $83,797, according to the National Association for Law Placement. In 2022, the salary was $116,398, a 39% increase. During that same time, tuition rose by only 26%, which was less than the 29% inflation rate.

The average debt of students who borrowed dropped from an estimated $112,000 to $111,000, according to U.S. News & World Report.

While that represents a decline of less than 1%, it is remarkable that it happened during a period when both tuition and inflation saw huge increases.

Most of this can be attributed to a dramatic increase in scholarships.

At University of Georgia, all first-generation college graduates and veterans receive financial assistance ranging from a modest stipend to a full tuition-and-fees scholarship.

“Every first-generation college graduate, or about 13% of the 165 students who started in the fall of 2023, got at least a quarter scholarship. And our veterans, who make up about 4% of the entering class, received some type of help as well,” Rutledge said. “The assistance we provide helps to ensure a diverse student body.”

Students can also receive help purchasing clothes and textbooks and may qualify for housing allowances.

In addition, University of Georgia students pursuing public interest or government careers can take advantage of summer fellowship stipends that may be offered for positions that are low-paying or unpaid.

“Over the last five years, we have provided roughly $1.3 million in assistance for those in unpaid summer legal positions at nonprofits, federal and state government, judicial clerkships, legal services and policy/impact organizations,” Rutledge said.

He noted that 44% of University of Georgia law students did not borrow money for the 2022-23 academic year.

Other Best Value law schools are also using scholarships to make legal education more affordable.

At University of Utah S.J. Quinney College of Law in Salt Lake City, 95% of the 2023 entering class received merit scholarships, up from 71% in 2019.

“We work hard to keep the price of attendance manageable, always keeping students in mind whenever we make decisions that potentially raise their debt,” said Dean Elizabeth Kronk Warner.

In-state tuition, including fees, for the 2023-24 school year is $33,634, while costs for nonresidents total $43,598.

“We want all of our graduates to leave the college of law feeling that it was time well spent in terms of their intellectual pursuits, skill set growth and personal development,” Warner said. “The monetary component is one way in which we measure the educational value we provide, but not the only way.”

For example, the school offers a host of resources that are designed to support and maintain students’ mental health. An onsite therapist is available for in-person or virtual meetings, and students have access to a mindfulness app and yoga classes, both free of charge. In addition, the school offers an optional, three-credit Mindful Lawyering course.

“We believe student debt can play a role in poor mental health, which is one of the reasons we work to keep costs as low as possible,” Warner said.

Seth LaPray, a second-year law student at the University of Utah, said the financial assistance he received and the individualized attention given to him during the application process were the main reasons he chose to attend.

“Before I even accepted the school’s offer, Associate Dean of Admissions Reyes Aguilar spent an hour on a Zoom call with me, answering my questions and explaining the financial assistance package,” said LaPray, who received a full tuition-and-fees scholarship.

Employment is king

While cost was a big selling point for LaPray, good employment opportunities sealed the deal.

“The proximity to downtown Salt Lake City provides access to a number of law firms,” he said. “I’m hoping to secure a position in one of the firms after I graduate.”

Ten months after graduation, the law school’s job placement rate for its Class of 2022 was 98%, Warner said.

“We’re proud of our high placement rate and proud of the fact that our students have the resources and support they need in order to pursue their dream careers,” she said.

preLaw uses a modified employment percentage, to determine both the quantity and quality of the legal jobs that each school’s graduates landed.

For example, we weight full-time jobs that require bar passage at 100%. Part-time jobs that require bar passage are weighted at 50%. A non-professional job, such as working at Burger King, is weighted at only 10%, and only if it’s full-time and long-term. (See full methodology on page xx).

Nationwide, employment for law school grads improved from 83% for the Class of 2021 to 86% for the Class of 2022, as legal hiring continued to improve despite warnings that it would reverse. It has steadily improved during the past 10 years. In 2012, it was 69%.

Our Best Value analysis is based on getting a legal job, and not on the prestige of that job. So, we do not assess salaries or types of employers.

We do look at salaries and employer types for our Best School for Law Firm Employment ranking that appeared in our Back to School issue and our Prestige ranking (see page 34 of that issue).

While employment figures have improved for all law schools, the Best Value law schools have taken active steps to improve at an even faster pace.

For example, in 2012, Texas Wesleyan University School of Law in Fort Worth recorded a modified employment rate of only 62%. Texas A&M University acquired the law school the next year, changed its name and adopted a much more systematic approach to engaging both students and prospective employers around post-graduate employment, said Dean Robert B. Ahdieh.

“With the students, we worked with them to define and refine their substantive and geographic interests, as well as other key priorities, to ensure we were supporting them most effectively,” he said. “With those insights in hand, in turn, we went to market to find the employers who ought to be hiring them.”

That, he said, helped improve employment results. For the Class of 2022, the school had the highest employment rate in the country for full-time, long-term, bar-passage-required or J.D.-advantage positions.

Texas A&M reported a 96% modified employment rate for the Class of 2022, earning it an A+ for employment in our ranking. Only a handful of law schools reported a better modified percentage, with the top school, Duke University, at 98.5%.

Its rise in employment outcome helped Texas A&M appear on our Best Value list for the first time in 2019, with a B+, and it has gradually risen since then. It is No. 16 this year, its highest position to date.

University of Utah recorded a 96% modified employment rate this year, up from 80% in 2012. It also has taken a more aggressive approach. Students are required to participate in a professional identity formation program, which focuses on cultural competence, mental health and career development.

“The program is run through our career development office and is mandatory for graduation,” Dean Warner said. “We invest a lot of time and energy into developing the entire student. This program is an integral part of that work, which ultimately helps with job placement.”

Students can also participate in clinics to gain experience and school credit or complete an externship at a law firm, governmental agency, nonprofit organization or business.

Stipends are available for public interest and government positions.

“We have added three positions to our career development office since I started in 2019,” Warner said. “Our staff meets with the students regularly to help them navigate their interests and secure positions.”

Since he enrolled at University of Utah in the fall of 2022, LaPray said, the career development office has been actively helping him with his job search.

“They listened to what I wanted and where I wanted to be and showed me the path I should follow to get there,” LaPray said. “They’ve helped me perfect my resume and held two or three mock interviews available to all students. The assistance has been invaluable.

“The staff is committed to my success, and because the school is affordable, I can focus on what I want to do after I graduate, not what I have to do to pay off my loan.”

Bar exam excellence

While the cost of legal education and employment rates have improved in the past 10 years, bar exam performance has been a little rockier.

In 2011, the average first-time bar passage rate was 79%, according to the National Conference of Bar Examiners. (This figure included test-takers who did not graduate from an ABA-accredited law school.)

The Class of 2011 entered law school in 2008, before the Great Recession and before law schools began admitting a higher number of students. By 2015, the bar passage rate had dropped to 70%.

The bar examiners group laid the blame on deteriorating student quality, claiming law schools had admitted too many students who didn’t have the intellectual chops for law school.

That led to a huge debate, as law school deans fired back, blaming the lower passage rates on the bar exam itself. Whatever the case, passage rates hovered around 70% for the next four years before rebounding to 73% in 2019 and 76% in 2020, according to the NCBE.

The debate led the ABA to start collecting its own bar passage data. It began to track what it called the ultimate bar passage rate, giving graduates from any given class two years to pass the exam. As expected, the ultimate bar passage rate, first reported for the Class of 2017, showed a higher percentage of success than the NCBE figures that counted only test-takers who passed the bar on their first try.

This year, the average ultimate passage rate was 91.87% for the Class of 2020, compared to a first-time passage rate of 83.66% for the same class, according to the ABA. Those figures are higher than the 79% reported by the NCBE for people who sat for the bar exam in 2020 and graduated from an ABA-accredited school.

Regardless of the cause, most agree that rates dropped around 2015 and rose again in 2019. But bar passage rates are still lower than they were for classes that entered law school before the Great Recession.

Meanwhile, which bar passage figures are the most meaningful?

For our ranking, we measured three data points for bar exam performance to account for various viewpoints on the matter.

First, we include the ultimate bar passage rate. This benefits schools with students who struggle to pass the exam on the first try. It is also the official measurement used by the ABA, which requires schools to report a 75% passage rate or risk losing accreditation. We assigned grades in this area on a scale, with any school at 75% or below receiving an F.

Second, we include the two-year difference between a school’s first-time passage rate and the state average. This helps law schools whose students take the bar in more challenging jurisdictions.

For example, in 2022, first-time test-takers from ABA-accredited schools who took the Florida bar exam had a 64% passage rate, but first-timers who took the Alabama exam had a rate of 83%. This data point makes up for the fact that in jurisdictions with higher passage rates it is harder for schools to perform above average.

Our third measurement point is the raw first-time two-year average pass rate. This benefits law schools who report high first-time passage rates, regardless of where their students took the exam. After all, most graduates just want to pass the exam and don’t care if their school got there because it is in a higher pass jurisdiction or because it’s in a jurisdiction like Wisconsin, which offers a diploma privilege.

This year, the average first-time bar passage rate dropped from 78% to 76%, and the median dropped from 80% to 75%. The ultimate bar passage rate remained the same. But many of the schools on our Best Value honor roll continued to improve.

University of Georgia reported that 99% of students in its Class of 2020 who sat for the bar passed it within two years of graduation.

To help ensure successful outcomes, the school provides summer stipends to students whose employers did not cover the cost of bar preparation.

In 2015, University of Georgia unveiled its BEST (Bar Exam Support Team) program in which students are paired with classmates so they can help motivate each other to complete all components of their summer bar-prep programs.

Run by the career development office, BEST is voluntary but many students take advantage of it, Dean Rutledge said.

Since 2020, University of Georgia students have been able to receive personalized legal writing assistance and practice test-taking strategies with the aid of an instructor during the summer.

“The combination of these techniques has boosted our bar passage rate over three years from the mid-90s to where it is now,” Rutledge said.

At University of Utah, the price of bar preparation materials is included in the tuition, so students don’t have to worry about paying for it separately.

“We have an agreement with Themis that significantly reduces what students pay for bar preparation,” Dean Warner said. “The cost is covered with tuition and divided over the six semesters that students are in law school.”

First-time bar exam takers from University of Utah have a passage rate of 94%, and those who have to take it again continue to have free access to Themis and school resources.

“We have a full-time faculty member who focuses exclusively on academic support, including bar passage,” Warner said.

Higher bar passage rates usually correlate with more robust employment numbers, and this has been the case for University of Georgia graduates. In 2021, only 79.6% of graduates had jobs lined up by graduation, while 93% of 2022 graduates had secured jobs by the time they received their diplomas.

“We believe that employment outcomes are directly tied to student indebtedness, which is why we do our very best to make sure that our students graduate with as little debt as possible,” Rutledge said. “If a student is heavily leveraged, it severely limits the individual’s freedom to accept lower-paying or public interest positions. We want our students to have the freedom to pursue their professional ambitions based on their passions, not their wallets.”

—Julia B. Johnson contributed to this story.

METHODOLOGY

How we calculate the Best Value Rankings

To determine our best value law schools, we assign a grade to every ABA-accredited law school for Bar Exam, Employment and Costs, and then weight each grade to determine a final GPA. Bar Exam is weighted at 15%, Employment at 30%, Costs at 55%.

To determine the Bar Exam grade, we look at three different data points: 1) Two-year difference between the first-time school bar pass rate and the average state rate (27% of bar exam grade); 2) Two-year ultimate bar pass average (53%); and 3) Two-year first-time raw bar pass rate (20%).

For Employment, we determine a modified employment rate for the two most recent classes. We use the ABA’s official employment statistics and weight each category to calculate the weighted average, not counting graduates seeking further education. Categories are weighed from 100% for Bar Passage Required: Full-time, Long Term, all the way down to 10% for Non-Professional position: Full-time, Long Term. Some categories are weighted at 0%, such as Non-Professional, Part-time.

For Costs, we use the tuition rate for in-state students and the lowest cost of living expense that a school provides to the ABA. We determine the total annual cost of attendance and assign grades on a grading curve. This represents 60% of the final Cost grade.

Average debt per student makes up the other 40% of the final Cost grade. We collected this data from U.S. News & World Report and estimated it when not available. Estimates were based on tuition, cost and debt averages and historical debt figures.